- 900 years of Klosterneuburg Abbey

- Abbey St Severin

- Benedictine Monastery Chantelle

- Benedictine Monastery Beuron

- Floral art

- Damascus steel

- The Grieser Klosteranger

- Kartäuser

- Ceramics from Maria Laach

- Kloster Neustift

- Königsmünster Monastery Bakery

- Monastery apiary

- Monastic work

- Food from Plankstetten

- Provencal olive oils

- Wines from Pforta Monastery

Gutes aus Klöstern

The Abtei St. Severin

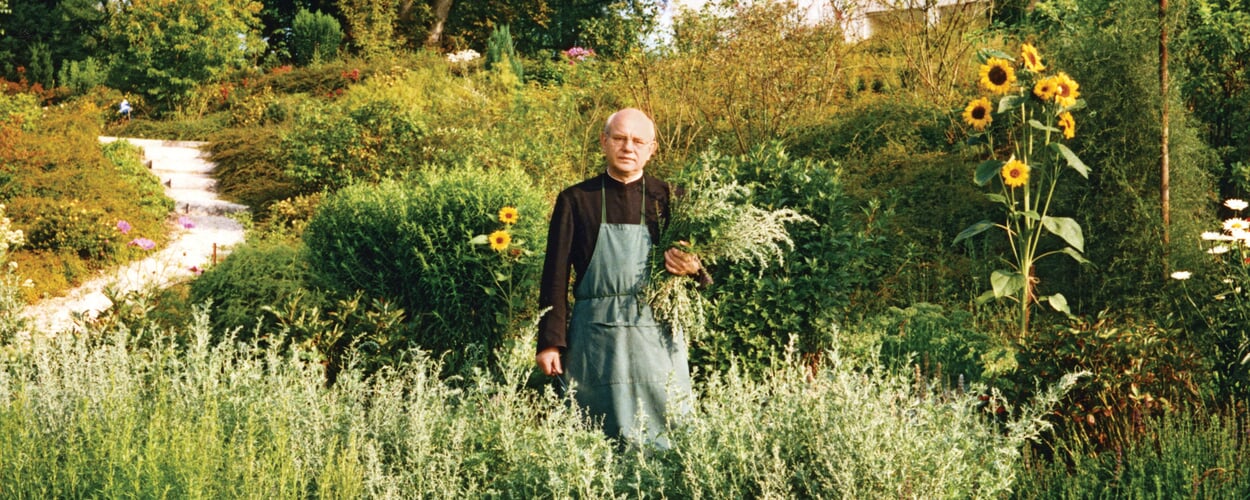

Every place has its magic and its troubles. When our monastery was still in Leinau, it was not possible to plant a classic monastery garden there due to the layout of the land and the geographical location. So for many years we tended a biotope wild herb garden, whose growing stock included many rare herbs from all over the world. The loss of our monastery building in 2010 meant that our community had to leave the garden behind with a heavy heart. With much effort, however, we managed to save about ninety percent of the plants.

It should become a monastery garden

Now we live on the heights above Kaufbeuren, and there the conditions are not there to create a similar garden as before. Our monastery is on the mountain, and the climate is much more severe. However, the move of the abbey to its present location opened up new possibilities for planning, since the terrain is wide and flat. Thus, the possibility of a classical monastic garden became apparent, and the convent has now decided to create a twelve-field monastic garden, as known from medieval monastic plans. Our order follows the rule of St. Benedict, who stipulated that everything that serves for the maintenance of the monks should be located within the monastic complex, if possible. On the one hand, this served to protect the community in times of war, on the other hand, the monastery was supposed to be an image of paradise, in the midst of the dangers and adversities of the "outside world". The monastery garden appears here in the image of a Garden of Eden, where everything grows that serves to provide for man. The number 12 had a particularly mystical meaning for the people of the Middle Ages, it represents the cycle of the year - 12 months, the time - 12 hours day, 12 night, the covenant of God with man: 12 tribes of Israel, 12 apostles, 12 gates at the heavenly Jerusalem. The 12 contains the two numbers of divine and cosmic perfection: 3 x 4. As a mirror of the divine order, the garden corresponds to a theology that can be experienced symbolically and sensually. Quite practically, the twelve fields are a navigational aid for the brother gardener and even the most simple-minded novice as to where to find which plants. In total, it will accommodate between 24 and 36 of the most important medicinal, spice and vegetable plants. With slight variations, they are still the same plants that are already listed in the "Capitulare de villis", the land ordinance of Charlemagne. In it, Charlemagne prescribed which plants were obligatory to grow in the gardens of his empire. One of the great poets of the Carolingian period, Walahfrid Strabo, refers to them; in his excellent didactic poem "Hortulus" he mentions: Sage, rue, boar's rue, gourd, melon, wormwood, horehound, fennel, iris, lovage, notch, lily, opium poppy, clary sage, lady's mint, polemmint, celery, medicinal zest, agrimony, tansy, catnip, horseradish, also the garden radish and the rose. These are plants that were useful for the purposes of supplying the monastery in the kitchen, pharmacy, bath and church and did not grow sufficiently wild or were not native. Everything else was either gathered wild or also grown in the additional orchards and fields of the monastery. In the center of the garden on a central axis will then be the cross as a reflection on the true Lord and Creator of the garden. As a former gardener (in my time before the monastery), I was often disillusioned because all the romantic ideas I had about a garden as a youth were abruptly disappointed. There it was all about industrial cultivation, efficiency and pecuniary exploitation of nature. In a monastery garden it is about harmony with creation, one gets to know the plants as sensitive beings. Here one learns to act in ecological responsibility, because we are only guardians, not masters of God's garden. With God's help, may our project succeed. Abbot Klaus OPR (†); Ecumenical Zisterzienserabtei St. Severin , Kaufbeuren

Monastery garden: memory of the lost paradise

Every garden touches on a longing that slumbers deep in the human heart, the longing for that primordial and happy garden of mankind's early days, the place of security and trust, where man's relationship with his God and Creator was still unbroken. Is it not this longing, this memory of the lost paradise, that has moved people throughout the ages to create and cultivate gardens? But what makes a garden, our garden, a world full of colors, scents and delicacies, a little paradise? Is it the well thought-out layout, is it the harmoniously coordinated plants in their different flowering and ripening periods? Is it the loving and painstaking care, is it the sun, wind, rain and dew at the right time? - All this is important, sure, but the actual always remains a miracle, the actual is not feasible.

And the man who walks through his garden with an awake and loving heart stands amazed before this miracle: Every year he joyfully welcomes the first winterling, which warms the still cold January days with its warm buttercup yellow, waits for snowdrops, primroses and violets to awaken from hibernation, spies out when a green glimmer finally indicates on the land, whether the carrot seed has sprouted, rejoices in the bloom of the summer flowers and the flight of the butterflies, carefully examines the ripening fruit, takes in the scent of the earth and the plants, hears the wind flowing in the arbor, and yet knows that even with all his effort he cannot get a bud to open. That it nevertheless does, that it matures into blossom and fruit, is the ever new miracle with which the garden gifts us. Sr. Christa OSB; Abtei St. Maria, Fulda

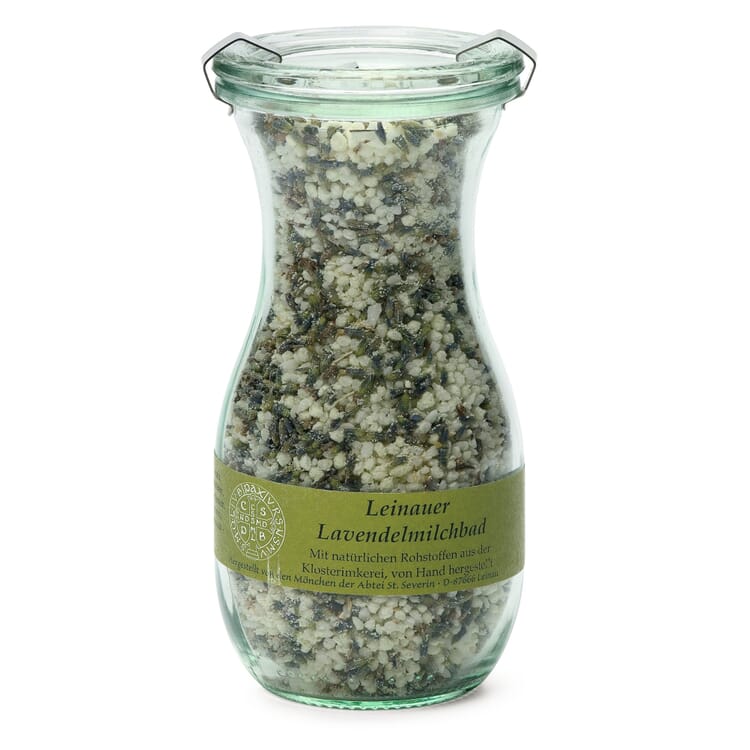

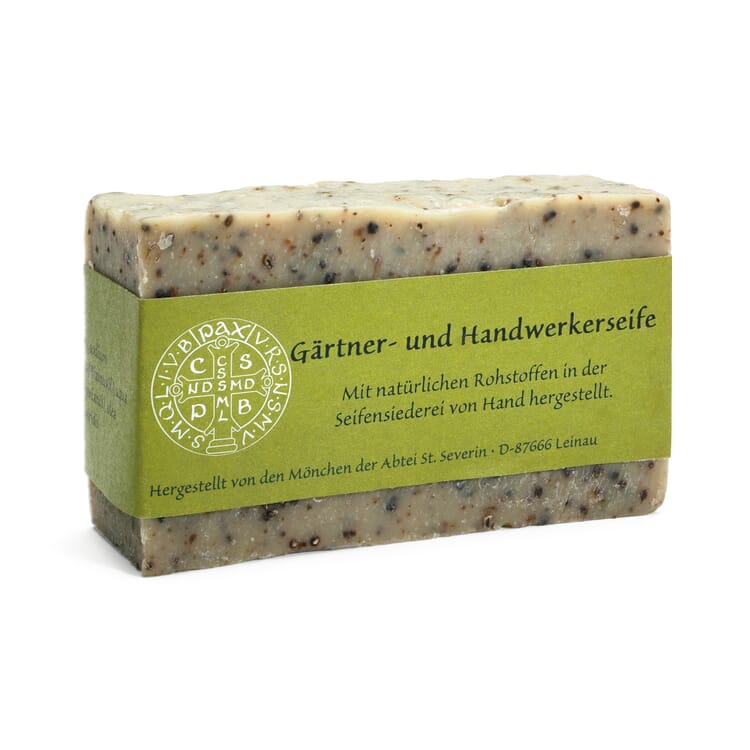

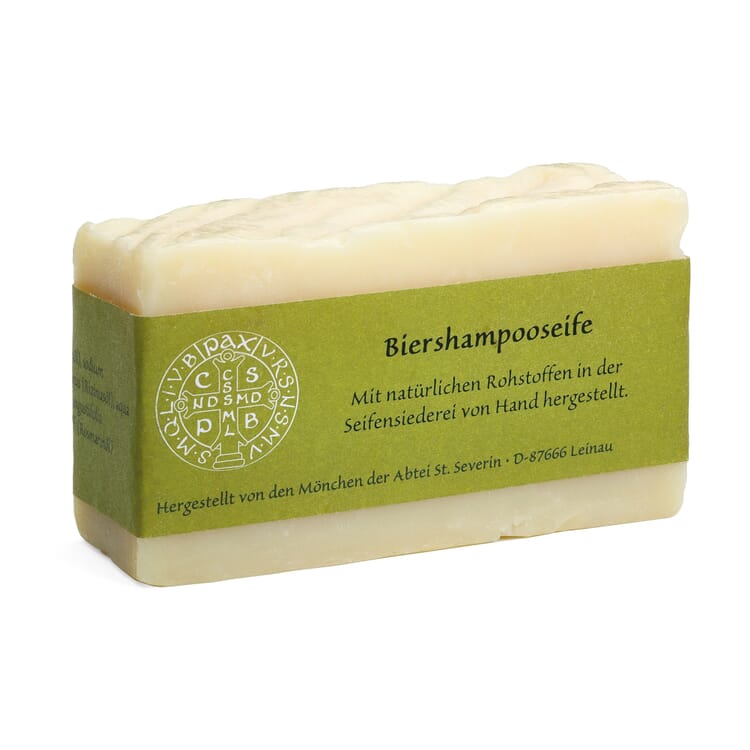

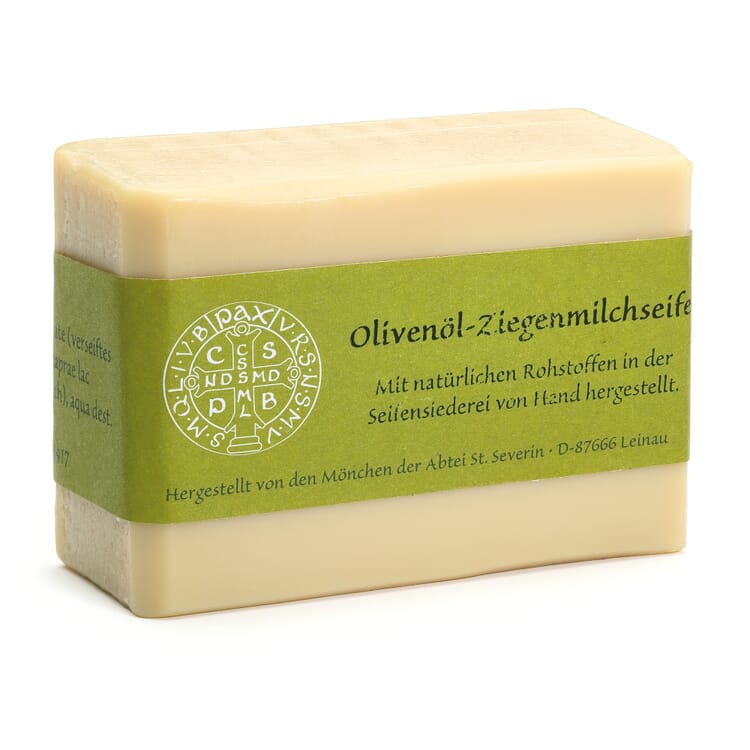

The products at a glance

The monks of St. Severin

In spring 2010, the Abtei St. Severin moved, and since then the three religious have been living in the former Bundeswehr radar school on the fresh, sunny (sometimes foggy) plateau above Kaufbeuren in the Bavarian Allgäu. They had to give up their former home in Leinau, which they had only rented, after a change of ownership. The monks of the abbey belong to the ecumenical Zisterzienserorder of Port Royal. In the 17th century, the name stood for a pious movement around Jansenism. This little spiritual ship never completely sank, even though it swayed vigorously back and forth between idea and deed and denominations, until it resumed monastic sailing in 1946.

And why should it not be symbolic that the monks have now found their harbor precisely here under a sea mark of aviation? They earn their living by offering spiritual courses and, above all, by producing soaps and other body care products. It is work that suits the monastic seclusion very well, because it requires not so much large machinery and equipment as concentration and attention to detail. This is evident to Br. George, who cuts the cast soap blocks into hand-sized pieces.